Author: Conservation Coordinator Shelby Serra

Nature-based experiences can contribute to individuals’ connection to nature and intentions toward sustainable environmental behaviors . —(Clark et. al. 2019)

After exploring the ins and outs of responsible wildlife-watching rules globally and in the US in the previous installment, we wrap up this series with a look at how Pacific Whale Foundation works to minimize the impact marine tourism can have on these incredible ocean animals.

Pacific Whale Foundation has been at the forefront of responsible whale watching for more than 40 years. Founded in 1980 by Greg Kaufman, a pioneer in non-invasive humpback whale research off of Maui in the mid-1970s, the young nonprofit spearheaded the use of scientific data and research to educate the public about whales and their ocean habitat. Over several decades, the Foundation tirelessly advanced its research, education and conservation work resulting in significant impacts in the conservation of humpback whales and other cetaceans.

A major contributor to the conservation of whales and dolphins is education surrounding human-cetacean interaction. Greg wanted people to be “face to fin” with whales in order to truly feel connected to them and discovered that boat-based whale watching was a way to both educate and inspire. Next was the birth of PacWhale Eco-Adventures (PacWhale), a social-enterprise model whereby Greg could take people out on a boat to “meet” the whales in a win-win situation where participants of this whale watch would continue to fund his whale research. Today, this innovative model provides stability to PWF’s research, education and conservation efforts allowing the organization to creatively and sustainably continue for another 40 years and beyond.

Since its inception, PWF’s extensive and diverse nonprofit work has contributed to the sustainability of responsible whale watching. Through our involvement with the International Whaling Commission (IWC), our role with the Hawaiian Islands Humpback Whale National Marine Sanctuary (HIHWNMS), and our global contributions to the identification of impacts of whale watching, PWF has established itself as a leader in the conservation of whales and dolphins.

Previously, we discussed the IWC’s history and contribution to marine tourism research. PWF researchers are members of the IWC Scientific Committee, a group of scientists from around the world that contribute to the body of science about the whales involved in this industry. Countries utilize this science to help implement regulations and guidelines for their respective whale-watching industries. Our presence on this committee gives us a seat at the table that literally drives the direction of the sustainability and viability of the industry.

In addition to these global efforts, PWF has positively impacted its birthplace — the Hawaiian Islands.

Although our reach today is global with projects in Australia, Ecuador and Chile, we were founded in Hawaii and therefore contribute to the work done within the sanctuary waters of the HIHWNMS.

This marine sanctuary, established by NOAA to offer protection to humpback whales, encompasses 1,400 of the most critical square miles of ocean surrounding the Hawaiian Islands. The Sanctuary formed an Advisory Council in 1996 that represents local user groups from six of the islands (NOAA) and PWF’s chief scientist, Jens Currie, represents the research chair.

Similar to the IWC scientific committee, the Sanctuary Advisory Council (SAC) provides advice to guide the sanctuary’s operations (NOAA). In November, the SAC formed a working group to discuss strengthening voluntary guidelines for humpback whales in Hawaii based on the best available science. These efforts will go a long way toward the continued protection of the humpback whales that utilize these winter breeding and calving grounds, further ensuring the conservation of this species.

In addition to a contributing presence on the SAC, PWF’s own Hawai’i research on the impact of vessels on humpback whale behavior (recently published) in conjunction with other research has highlighted the need for stricter guidelines when approaching whales, as vessels traveling at fast speeds (>6 knots) in close proximity (within 400 yards) to humpback whales can cause a change in whale behavior. This extra energy expenditure can negatively impact the animal’s health and highlights the need for vessels to follow appropriate whale-watching guidelines.

Our most recent research identifying spinner dolphin movement and behavior patterns has illuminated the need for additional protection during the animals’ resting hours (daytime). PWF research has proposed that the identified hotspots be considered as additional sites for timed closures, in addition to an approach limit for vessels transiting Maui Nui (Stack et. al).

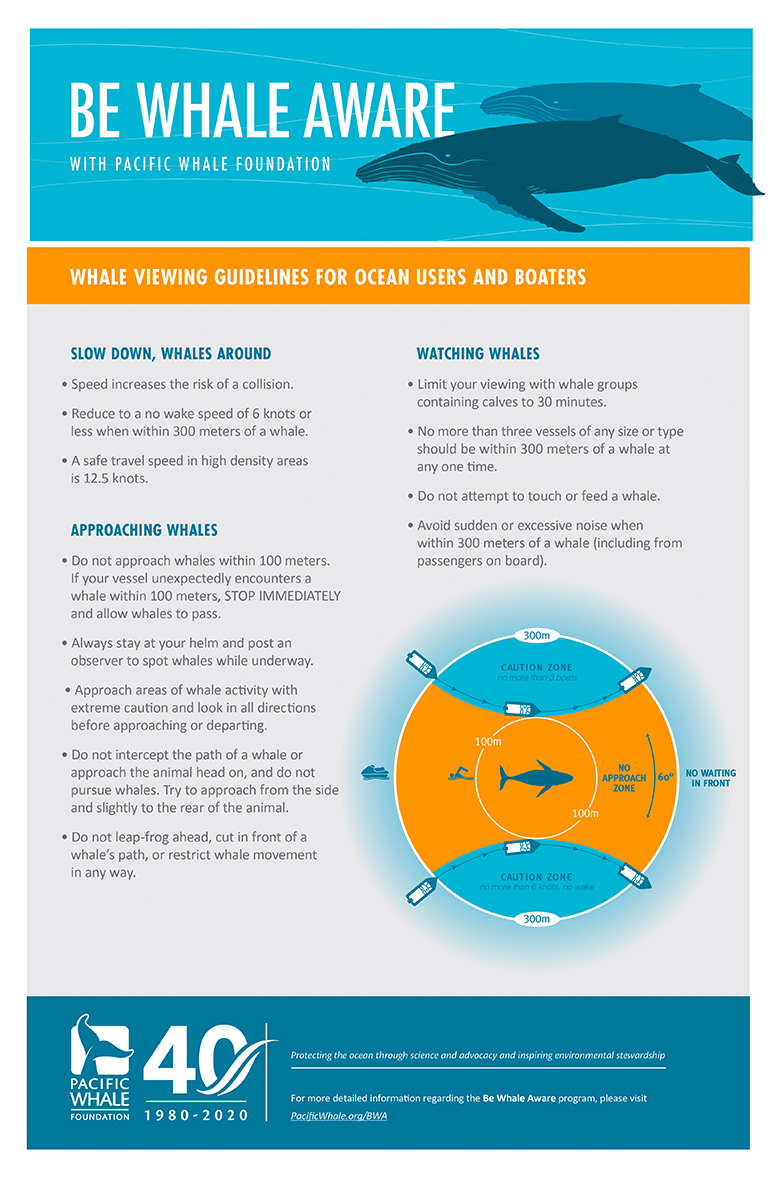

This, and other in-house research, has prompted the creation of a stricter set of guidelines (“Be Whale Aware”) for PacWhale Eco-Adventures vessels to follow.

One of the biggest differences between PWF guidelines and federally enforced guidelines are the speed limits. Currently, the only speed limit regulation is for vessels 65 feet or larger to travel at speeds less than 10 knots at specific locations along the U.S. eastern seaboard (Silber et. al.). This regulation exists because the area is the habitat of the critically endangered Northern right whale. Our “Be Whale Aware” guidelines also stipulate that there be no more than three vessels watching a whale at any time. Compliance of this guideline follows a “three and flee” rule, whereby PacWhale vessels will depart the area if there are three vessels (besides their own) viewing one whale or one group of whales at a time. These guidelines are also advocated by our research team working out of Machalilla National park in Ecuador, in hopes that the whale-watching industry in that part of the world can continue to be both beneficial to the whales and sustainable for the local economy.

Further contributing to our global wildlife conservation efforts, PWF has just wrapped a third season in Hervey Bay, Queensland, Australia studying the impacts of an emerging form of wildlife tourism — swim-with-whales.

In 2014, the Queensland government authorized commercial tourism companies to begin immersive swimming activities with humpback whales, currently listed as a “vulnerable” species under the Australian Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act. The purpose of the Swim-With-Whales Impact Study is to assess the impact of immersive whale watching (or swim-with-whales tourism) on humpback whales in Hervey Bay by monitoring and recording behaviors and behavioral changes of the animals involved. These findings will provide managers with insight into the potential impacts of this activity and recommendations for local tour operators.

Pacific Whale Foundation has long been an innovator in whale conservation and confidently holds the position of thought leader in responsible whale watching. Our research continues to contribute to the conservation of the species, and our emphasis on education on board PacWhale Eco-Adventures vessels allows us to lead by example. Pacific Whale Foundation has set the precedent for responsible whale watching, educating and inspiring nearly 400,000 people a year through our nonprofit programs and social enterprise, PacWhale Eco-Adventures eco-tourism company. We look forward to another 40 years of research, advocacy, education and innovation to help ensure a bright future for whales and their natural habitat.

Sources

- Stephanie Stack, Grace Olson, Valentin Neamtu, Abigail Machernis, Robin Baird, Jens Currie “Identifying spinner dolphin Stenella longirostris movement and behavioral patterns to inform conservation strategies in Maui Nui, Hawaii” Marine Ecology Progress Series, 2020

- Eleanor Clark, Kate Mulgrew, Lee Kannis-Dymand, Vikki Schaffer & Rosie Hoberg “Theory of planned behaviour: predicting tourists’ pro-environmental intentions after a humpback whale encounter”, Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 2019

- Gregory Silber, Jeffery Adams, Christopher Fonnesbeck “Compliance with Vessel Speed Restrictions to Protect North Atlantic Right Whales.” Noaa.gov, 2009

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, NOAA